La Carte Postale, by Anne Berest

Reviewed by McKenzie Watson-Fore

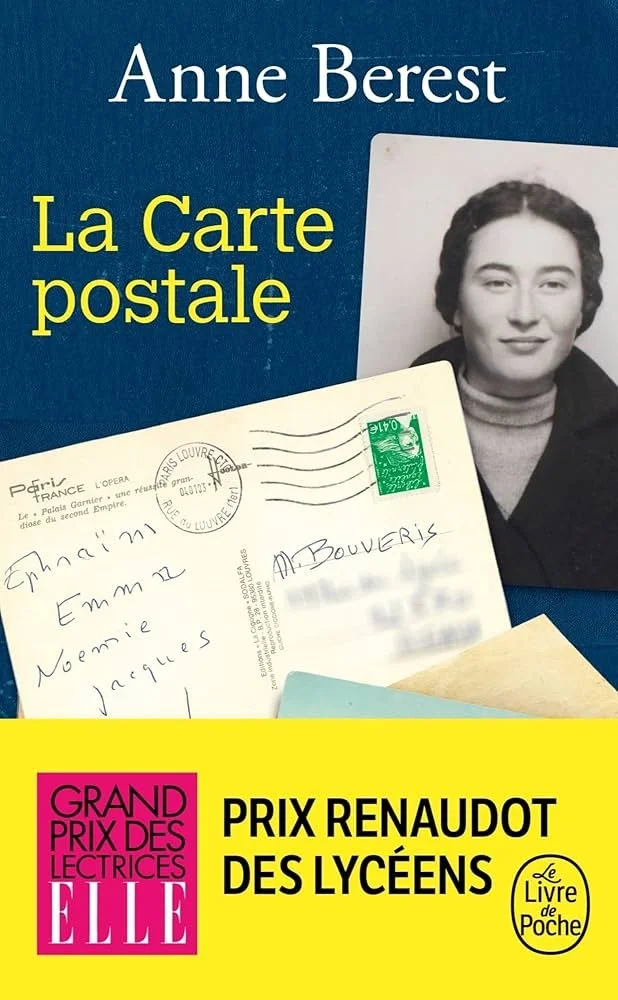

Anne Berest. La Carte Postale. Grasset, 2021 (French). Released in the U.S. in 2023 (Europa Editions). ISBN 9782253937708

One Monday morning in January 2003, Lélia receives an anonymous postcard bearing nothing but four names—Ephraïm, Emma, Noémie, Jacques: the names of Lélia’s maternal grandparents, aunt, and uncle, all of whom died in Auschwitz in 1942. The circumstances surrounding this mysterious postcard, and the lives and deaths of those named on it, constitute the story of La Carte Postale, by French novelist Anne Berest.

Berest is Lélia’s daughter. She is 24 when the postcard arrives and can’t be bothered with long-forgotten family drama. “I had my head occupied with a life to live,” Berest says. The myopia of youth often occludes historical concerns. But her disinterest in her family’s history is temporary. Ten years later, during the final weeks of a difficult pregnancy, Berest is placed on bedrest, which she spends at her parents’ home. “In that suspended state,” Berest recalls, “I thought of my mother, of my grandmother, of the line of women who had given birth before me. Such is how I felt the need to hear the tale of my ancestors.” For the remainder of Book I—some 225 pages—Berest listens to her mother, Lélia, recount the fates of her forebears.

Lélia starts the story in 1918, Russia. Her grandparents, Ephraïm and Emma, are Jews from Moscow and Lodz. Ephraïm sees himself as a Russian, having renounced his family’s religion and proclaimed himself a socialist. “He wants to participate in the grand adventure of progress, he has high ambitions for his country and for his people, the Russian people, whom he intends to join in the Revolution,” Lélia recounts. In spite of their repeated attempts at assimilation, the Rabinovitch family is never truly accepted by their countrymen, either in Russia or elsewhere. Nachman, Ephraïm’s father, tells his family early in the book that they must leave the country. He pleads with his adult children to join him in moving to Palestine, because Nachman’s lifelong acquaintance with antisemitism warns him that their acceptance in Russia is waning. “It’s like an acrid odor in the air, like a cold wind that announces the coming freeze.”

Ephraïm and his young wife, Emma, pregnant with Myriam, Lélia’s mother, move not to Palestine but to France. Ephraïm is determined to succeed in the commercial markets of western Europe, and he rebuffs his father’s concerns. “The worst that’ll happen to you here is if your tailor becomes a socialist!” Of course, anyone reading the book is aware of the dark dramatic irony and wishes Ephraïm had been right.

One of the most chilling aspects of reading La Carte Postale was watching its characters—notably, Ephraïm and Emma—ignore the creeping signs of fascism. They are happy in Paris, Ephraïm insists, and he believes that his ultimate professional success is always just around the corner. Acknowledgement of the shifting political tides would have likely require Ephraïm to abandon his dreams, too high a cost. The grand sweeps of history often seem to unfold in the periphery, until they cannot be elided any longer, which is what happens to the Rabinovitch family.

Ephraïm fumbles every opportunity to flee France and move his family to safety. In one heartbreaking scene, he meets up with Anna Gavronsky, the woman he really loved before his family intervened and arranged his marriage to Emma. Aniouta, as he refers to her, has just fled Berlin, and she recounts to Ephraïm the terrible events of Kristallnacht, which occurred the week before. The Nazis came for Aniouta’s husband. From Paris, she plans to travel with her young son to Marseille, and then depart for New York as soon as possible. Ephraïm hopes that his Aniouta has come to beg him to accompany her, but instead, she exhorts him to find a way to leave with his own family. “I contacted you to warn you,” she says. “If Adolf Hitler succeeds in conquering Europe, we won’t be safe anywhere. Anyway, Ephraïm! Do you hear me?” But he is distracted by his feelings over their thwarted romance. Wounded, he salves his dignity by seeking to discredit her warnings. “Of course, what’s happening in Germany is terrible…but Germany isn’t France. She’s mixing it all up,” he says.

While reading, I found it almost impossible not to draw parallels between the rise of fascism in Europe in the 1930s and what’s happening right now in the United States. The global audience, watching constantly through our smartphones, is practically inundated with signs of the rising authoritarianism, and yet public outcry seems out of step with the looming threat.

Student protestors and dissenters have been disappeared and deported. Peaceful protests have been shut down via federal intervention. The national guard has been deployed in our cities. The United States president has unilaterally exerted his executive power to override other government agencies and demote the heads of allegedly independent bodies that exist to prevent executive creep. Federal agencies have been given nearly boundless authority to stop individuals, often solely on the basis of personal bias or skin color, and legal residency has been revoked over the question of free speech. Whatever checks and balances were once put in place to protect against the threat of presidential overreach are being torn down—actively dismantled—by Trump and his cronies.

Once France was taken over by Nazi Germany, circumstances immediately and irrefutably changed. Ephraïm and Emma move themselves and their children to a country house in the village of Forges, outside of Paris, but they do not distance themselves enough. Myriam, the oldest child of the Rabinovitch family, meets a young man named Vicente and they fall in love. The two marry quickly, in November 1941, in a simple courthouse ceremony. This causes Myriam’s name to be scratched from the list of Jews living in the department where her family is, and transferred to the (much longer) list of Jews living in Paris. But one night, Myriam and her husband are drinking at a rum bar with their friends past curfew, and Myriam is apprehended by the police. Somehow, after spending two nights in jail, Myriam is released, for reasons she does not fully understand. She leaves Paris and heads to the family home in Forges.

The writing in this book is gorgeous. Scenes are rich and sensual, capturing the vibrant, many-hued experience of being alive. The vivacity in Berest’s writing contrasts with the flat evil of the Nazi regime and their final solution. While Myriam is back home, the family celebrates Jacques passing the first portion of his baccalaureate. He and his sister, Noémie, have been out riding bikes during the day; at dusk, the family dines together in the backyard.

“All five of them are in the same places around the table where they sat in Palestine, in Poland, then in Paris on Amiral-Mouchez Street—this table is their ship. The night looked like it no longer wanted to fall, and the garden air was still full of the sugared heat of the day.”

Is it always in moments of such happiness, such seeming imperviousness, that something terrible happens to change the course of all that is to come? Two police cars arrive at the Rabinovitch home in Forges: one vehicle holds three German soldiers; the other, two French gendarmes. They come seeking the children: Noémie, age nineteen; and Jacques, sixteen. Ephraïm Rabinovitch begs the officers to take him instead, but they brush him off. “They must be sent to work. No one will cause them harm. You will be kept updated.”

Berest asks her mother why the youths were taken without their parents, and Lélia explains the multiple waves of deportations, starting with young men, then all young people, parents with children, and finally the elderly. This was the Nazi strategy to suppress concern while eliminating those most likely to resist.

Of course, the reassurances proffered by the gendarmes are lies. The two Rabinovitch children are taken to Pithiviers, an internment camp in north central France. The prisoner who fills the role of camp doctor, Adelaide Hautval, conscripts Noémie to serve as her physician’s assistant. Once again, Berest interrupts to ask how Lélia could possibly know this.

“I’m not inventing anything,” Lélia replies. “The doctor Adelaide Hautval really existed, she wrote a book after the war, Medecine and Crimes Against Humanity.” Lélia reads her daughter a passage in which Dr. Hautval describes Noémie Rabinovitch as “my best collaborator.”

“Her book is not the only testimony about Noemi I’ve found,” Lélia adds. “She marked people, wherever she went.”

The amount of research and documentation that Lélia assembled to reconstruct her family’s history is staggering. Everything she relays is documented. “Everything I know, I’ve reconstituted thanks to the archives, reading books, and also because I’ve found certain drafts in the things of my mother’s after her death,” Lélia explains. La Carte Postale reminds readers of the incredible amount of work required to refute the erasure of the Holocaust and the Nazi Regime, and how much is still unknown. Thanks to her research, Lélia is able to trace the story of her four family members all the way to their deaths. The single surviving Rabinovitch, Lélia’s mother Myriam, “never recounted their stories in her lifetime.” Once Lélia reaches the end of her recitation and stands to go get a fresh pack of cigarettes, her daughter’s water breaks.

The book picks up when Berest’s daughter, Clara, is six. Clara has told her grandmother, Lélia, that “they don’t like Jews too much at school.” Berest, uncertain how to handle this secondhand revelation, draws the reader deeper into the family’s intergenerational wrestling with an ethnoreligious identity that one has not chosen but one cannot disavow. Instead of asking her daughter about the incident, Berest’s mind fills with the image of the postcard. She vows to finally uncover who sent the anonymous missive to her family, and why.

For the remainder of the book, these two pursuits wind around one another. Lélia is reluctantly conscripted into Berest’s quest to find the origin of the postcard, while Berest assembles her own memories of how she came to understand her Jewishness.

The memoir is narrated with incredible immediacy. One comes to see how Berest’s quest regarding the postcard develops into an obsession that colors her days and occupies her subconscious, even as she continues in her regular activities. And yet, her fixation with her family’s history also infuses her daily exchanges, prompting her to consider afresh how she’s interpreted her Judaism throughout her life and what it means to her. These questions come to a head when she attends a Passover dinner hosted by her boyfriend, Georges, who may have assumed Berest to be more observant than she actually is. However, Georges’ close friend and former flame Deborah, also in attendance, clocks Berest’s ignorance and wields her awareness like a weapon. By the end of the meal, Deborah levels her final assessment of Berest: “In fact, if I’m understanding correctly, you’re only Jewish when it suits you.”

Berest doesn’t bother to respond to Deborah, but she does write a letter to Georges, outlining her experiences of Judaism. After the war, Berest writes, Myriam “never again entered a synagogue. God died in the death camps.” Lélia raised Berest to put her faith in social change movements rather than religion. Gradually, Berest comes to feel that the liberal values she was taught stand in mild contradiction to their family history as Jews. “In the middle of the Enlightenment discourse I was taught, there was this word that kept coming back like a black star, like a strange constellation, clothed in a halo of mystery. Jewish.” These contradictions—the complications of growing up maligned for an identity one does not even understand—fuel Berest’s investigation.

The horizons traversed by this book are extensive: Berest explores sexuality, secrecy, prejudice, and more. Startling intergenerational coincidences suggest intangible connections that ripple across time and space. I read the book like it was a thriller, both electrified and perturbed by its truth value. Berest, who has written several novels and one play, describes La Carte Postale as a “nonfiction novel,” rooted in history, but with select details altered and reimagined.

The book’s twists and turns kept me breathless, but rather than removing me from the world, it fueled my commitment to staying engaged with the developments in US and global politics. Escapism and ignorance will not save us, the book illustrated. Unlike Ephraïm, we must stay alert to where rights are being repealed, to wherever movement is restricted, and to whenever individuals are being disappeared. We cannot accept an untrustworthy government’s word that they will not betray us. And we must agitate for justice for those who have already been betrayed by our silence.

McKenzie Watson-Fore is a writer, artist, and neighbor currently based in her hometown of Boulder, Colorado. McKenzie holds an MFA in Nonfiction from Pacific University. She writes about evangelicalism, relationships to people and place, and self-discovery. McKenzie serves as the executive editor for sneaker wave magazine and is the founder and host of the Thunderdome Conference. Her work has been nominated for Best of the Net and Best American Essays. She can usually be found drinking tea on her back porch.